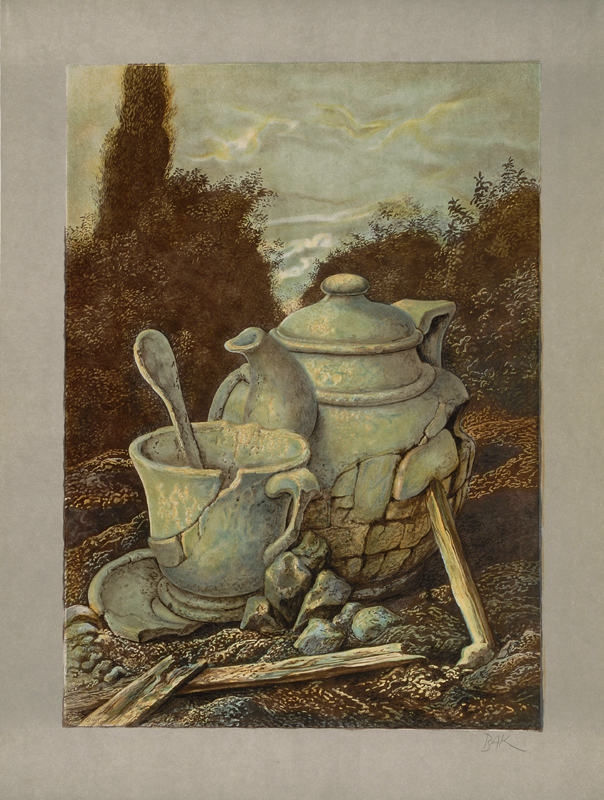

Shemuel Bak

Bak Shemuel

Tea Pot

$400

19" x 26" Lithograph 1971 Edition 150

Shipping & Handling: $30

Samuel Bak was born in Vilna, Poland in 1933. His immense artistic talent was recognized early; the artist was only five years old when he was encouraged to dedicate his life to art by his great-uncle, Arno Nadel, the Jewish poet, painter and musician. The Nazi occupation of Vilna in 1940 interrupted those early aspirations. However, Bak was able to hold his first exhibition of drawings in the Vilna Ghetto in 1942. A year later, he and his parents were marched off by the SS to the HKP camp on the outskirts of Vilna, where his father was shot just a few days prior to the Russian liberation of the city. Bak was one of the 150 Vilna Jews who survived the war – out of a Jewish community of 80,000.

The trauma of the Holocaust had a tremendous influence on Bak’s later artistic works. As the artist himself explained: “For me, it is important to tell the story of that moment in my childhood when everything was disintegrated – despite arrangements for safety and protection. Nothing was sure anymore, only the knowledge that in a day, perhaps two, we would cease to exist.” The story that the artist wishes to relate, however, is so grotesque that he prefers the use of symbols. “Instead of speaking of people, I paint fruit, and somehow this helps me to get nearer to my subject.”

After the war, Bak and his mother attempted to reach Palestine, and Bak continued his artistic education whenever he was able. In 1948, the artist embarked on an illegal journey to Palestine through France, arriving in the newly established state during the War of Independence. During the next few years, Bak studied at the Bezalel Art School in Jerusalem, served in the army, and designed scenery.

Bak describes his mode of work as “a style founded on the classical tradition” where “the contents have remained linked to the spirit of our age and express its anguish.” He developed this style gradually, after experimentation; with “totems”, abstract figures in space; lyrical abstractions, especially beautiful in their subtle treatment of light and atmosphere; structural abstractions; relief-like collages; and a handsome and mysterious group of “labyrinth” paintings, from which stemmed Bak’s metaphysical, surrealistic works. Bak realizes that his style contradicts the age, but feels it fully his own. “There is danger,” the artist has claimed, “in just drifting along with current trends, in exerting false pressure to keep up to date. When one has to change every year, to hold the antennae erect and tuned in to fashion, where is the time for self-improvement? In fact, a lifetime is required to bring one form of art to perfection.”

While critics initially labeled Bak a ‘traitor’ for his ‘reactionary works’, Bak felt relief rather than apprehension in pursuing his own path. “I paint because art has the power to save me as an individual – to give me an identity in an epoch when individuality is being more and more suppressed by prefabricated systems.” And he feels that this identity can be most fully realized by his use of the classical style: “the classical direction would be the one to offer me all that I loved, wanted and so much enjoyed seeing in works of past centuries, and also in works bearing their influence.”

To understand Bak’s works, one must understand the symbols which the artist uses so freely. His three most central images are those of pears, chessmen and keys. Why did Bak choose these for his symbols, and what do they mean to him? “I chose the pear for its neutral features, deceptively neutral like the surface of everyday life and smooth like the skin of a pear. But give it a gentle scratch and see what a fearful world lies hidden just underneath! The chessmen stand for Rationality. They speak of the absurdity of war and of failure of the rational approach to prevent war and poverty.” The key motif, claims Bak, is unlike the pear, in that it “comes on the scene with firmly established connotations, a familiar symbol of man’s need to find explanations, to search for the meaning and find answers to the fundamental questions of existence.” It is these multi-faceted answers to the multitude of questions that Bak is trying to reach in his works: “As I am not very orthodox, my paintings pose multiple questions and seek numerous answers.

Bak Shemuel

The Unfinished Game

$28000

29 inches wide x 21 inches high 73.5cm wide x 54.5cm high Oil on Canvas

Shipping & Handling: $30

Samuel Bak was born in Vilna, Poland in 1933. His immense artistic talent was recognized early; the artist was only five years old when he was encouraged to dedicate his life to art by his great-uncle, Arno Nadel, the Jewish poet, painter and musician. The Nazi occupation of Vilna in 1940 interrupted those early aspirations. However, Bak was able to hold his first exhibition of drawings in the Vilna Ghetto in 1942. A year later, he and his parents were marched off by the SS to the HKP camp on the outskirts of Vilna, where his father was shot just a few days prior to the Russian liberation of the city. Bak was one of the 150 Vilna Jews who survived the war – out of a Jewish community of 80,000.

The trauma of the Holocaust had a tremendous influence on Bak’s later artistic works. As the artist himself explained: “For me, it is important to tell the story of that moment in my childhood when everything was disintegrated – despite arrangements for safety and protection. Nothing was sure anymore, only the knowledge that in a day, perhaps two, we would cease to exist.” The story that the artist wishes to relate, however, is so grotesque that he prefers the use of symbols. “Instead of speaking of people, I paint fruit, and somehow this helps me to get nearer to my subject.”

After the war, Bak and his mother attempted to reach Palestine, and Bak continued his artistic education whenever he was able. In 1948, the artist embarked on an illegal journey to Palestine through France, arriving in the newly established state during the War of Independence. During the next few years, Bak studied at the Bezalel Art School in Jerusalem, served in the army, and designed scenery.

Bak describes his mode of work as “a style founded on the classical tradition” where “the contents have remained linked to the spirit of our age and express its anguish.” He developed this style gradually, after experimentation; with “totems”, abstract figures in space; lyrical abstractions, especially beautiful in their subtle treatment of light and atmosphere; structural abstractions; relief-like collages; and a handsome and mysterious group of “labyrinth” paintings, from which stemmed Bak’s metaphysical, surrealistic works. Bak realizes that his style contradicts the age, but feels it fully his own. “There is danger,” the artist has claimed, “in just drifting along with current trends, in exerting false pressure to keep up to date. When one has to change every year, to hold the antennae erect and tuned in to fashion, where is the time for self-improvement? In fact, a lifetime is required to bring one form of art to perfection.”

While critics initially labeled Bak a ‘traitor’ for his ‘reactionary works’, Bak felt relief rather than apprehension in pursuing his own path. “I paint because art has the power to save me as an individual – to give me an identity in an epoch when individuality is being more and more suppressed by prefabricated systems.” And he feels that this identity can be most fully realized by his use of the classical style: “the classical direction would be the one to offer me all that I loved, wanted and so much enjoyed seeing in works of past centuries, and also in works bearing their influence.”

To understand Bak’s works, one must understand the symbols which the artist uses so freely. His three most central images are those of pears, chessmen and keys. Why did Bak choose these for his symbols, and what do they mean to him? “I chose the pear for its neutral features, deceptively neutral like the surface of everyday life and smooth like the skin of a pear. But give it a gentle scratch and see what a fearful world lies hidden just underneath! The chessmen stand for Rationality. They speak of the absurdity of war and of failure of the rational approach to prevent war and poverty.” The key motif, claims Bak, is unlike the pear, in that it “comes on the scene with firmly established connotations, a familiar symbol of man’s need to find explanations, to search for the meaning and find answers to the fundamental questions of existence.” It is these multi-faceted answers to the multitude of questions that Bak is trying to reach in his works: “As I am not very orthodox, my paintings pose multiple questions and seek numerous answers.